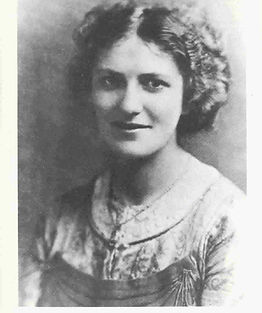

Jessie Chambers

'The girl had launched me, so easily, on my literary career, like a princess cutting a thread, launching a ship.' D.H. Lawrence

'The consequences of the impact of these two on each other was profound and far reaching, and has never had adequate justice done to it in the Lawrence story.' J.A. Bramley

5 reasons why we won't forget Jessie Chambers

1. ‘the chief friend of my youth’

is how Lawrence describes Jessie Chambers in an ‘Autobiographical Sketch’ in 1929. As his childhood friend and first girlfriend she played a vital role in his journey.

Jessie Chambers, born on the 29th January 1887 - a year younger than DH Lawrence, was eleven years old when her family left Eastwood to go to live at Haggs Farm, Underwood, three miles away. Mrs Chambers invited Mrs Lawrence to visit and the rest is history, set down by Lawrence in Sons and Lovers.

Jessie, one of seven children, left school at thirteen in order to stay at home to help her mother look after the family. But she was determined to escape into a wider life. She had a passion for reading and would recite the poems of Scott to such a great length that she often bored her brothers with her intense recitations.

Jessie became a pupil teacher at Underwood School and then went to the Ilkeston Centre to get her teaching certificate. It was a strenuous routine walking the three miles each way to Langley Mill Station twice a day, carrying armfuls of books for her homework. Lawrence was already at the centre and knew Jessie from the Congregational Chapel at Eastwood. He helped her tackle maths, geometry, algebra and French, and together in the little alcove in the kitchen at the Haggs they would read Dostoevsky, Anatole France, Hardy and Tolstoy.

The Chambers family outside Haggs Farm - Jessie is front right.

‘Then, in the doorway suddenly appeared a girl in a dirty apron. She was about fourteen years old, had a rosy dark face, a bunch of short black curls, very fine and free and dark eyes; shy and questioning, a little resentful of the strangers, she disappeared.’ Sons and Lovers

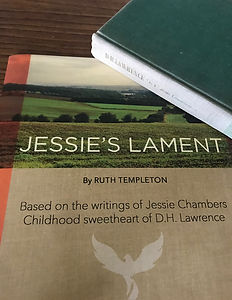

Jessie by

Ruth Templeton

2. Emily Saxton and Miriam Leivers

Lawrence portrays Jessie vividly in two of his early novels – as Emily in The White Peacock and Miriam in Sons and Lovers.

'The shawl she had been wearing was thrown across her shoulders, and her head was bare, and her black hair, soft and short and ecstatic, tumbled wildly into loose light curls. She thrust the stalks of the berries under her combs. Her hair was not heavy or long enough to have held them. Then, with the ruby bunches glowing through the black mist of curls, she looked up at me, brightly, with wide eyes. I looked at her, and felt the smile winning into her eyes. Then I turned and dragged a trail of golden-leaved convolvulus from the hedge, and I twisted it into a coronet for her.

"There!" said I, "you're crowned."

She put back her head, and the low laughter shook in her throat.'

The White Peacock

'All the life of Miriam’s body was in her eyes, which were usually dark as a dark church, but could flame with light like a conflagration. Her face scarcely ever altered from its look of brooding.'

Sons and Lovers

3. 'The girl had launched me, so easily, on my literary career...'

Jessie Chambers can be credited with launching Lawrence’s literary career; at first she helped and encouraged him, reading his work and giving him the support he didn't get anywhere else. Then she began to recognise his genius and it was she who collected his early poems and scraps of writings, copied them out and sent them to the English Review where Ford Madox Hueffer (Ford) agreed to publish.

4. ‘the anvil on which I hammered myself out’

Jessie sets aside a whole chapter in A Personal Record to describe the extent of their reading together. ‘Then Lawrence and I would set off for my home literally burdened with books. During the walk we discussed what we had read last, but our discussion was not exactly criticism, indeed it was not criticism at all, but vivid recreation of the substance of our reading. Lawrence would ask me in his abrupt way what I thought of such and such a character, and we would compare notes and talk out our differences. The characters interested us most, and there was usually a more or less unconscious identification of them with ourselves, so that our reading became a kind of personal experience.

This period when Lawrence would be 16-17, was a kind of orgy of reading. I think we were hardly aware of the outside world.’

It’s easy to picture the two of them walking across the fields, arms full of books, deep in discussion about this character and that. Of course, Lawrence inspired Jessie but her enthusiasm spurred him on and her insights developed his. Jessie read all of Lawrence's early work, writing careful thoughts and corrections in the margins. Even when he was teaching in Croydon, he was still sending the manuscript of Sons and Lovers to her for proof reading and correction and it was she who suggested he should write more honestly about his past. Unfortunately as the novel developed she became increasingly disturbed by his portrayal of her and their relationship. As Ann Howard recalls:

'My father remembered watching her as she read the manuscripts, writing her comments carefully at the side before sending them back to him. Lawrence rejected her advice completely, insisting on including all the things which she had begged him to alter or omit...'

5. A Personal Record

Coincidentally both Jessie and Lawrence wrote short stories, based on the same subject matter, within a few years of each other. Lawrence's short story 'Goose Fair' published in 1914, highlights the plight of the framework knitters in Nottingham in the early 19th century. This downturn in trade was the reason behind the suicide of Jessie's great grandfather in 1826 and subsequently led to her grandmother, Jane being brought up by the wealthy Morley family, founders of I & R Morley, hosiery manufacturers. Jessie's short story, 'The Bankrupt' originally written in 1910 is based on this family tragedy. Helen Corke, a friend of Jessie and Lawrence, suggested amendments to the drafts and then in 1912, on behalf of her friend, submitted the manuscript to the editor of the English Review. It was favourably received but not published.

Jessie also wrote her own version of the Miriam and Paul story in a novel entitled The Rathe Princess under the pseudonym Eunice Temple but when it was rejected, she burnt it, together with all the letters she had received from Lawrence. Once Lawrence had died, Jessie started to write 'D.H Lawrence: A Personal Record'; it was published in 1935 under the initials E.T. and is a sensitive and insightful account of their friendship.

'The narrative is of an early friendship, in many ways idyllic, which suffered shipwreck for reasons beyond the control of the protagonists. Its value lies not only in the convincing portrait of the youthful Lawrence but in the sincerity, reticence and imaginative understanding implicit in the telling.'

Max Plowman, 1935

What happened next?

Jessie cut all ties with Lawrence after reading his portrayal of her as Miriam in Sons and Lovers. In 1913 she met Jack Wood, a farmer’s son and fellow teacher. They were married in 1915 and for the next few years their lives were of course dominated by the war. Jessie taught and continued her own studies which included Russian, and had many literary friends. She had always been left wing in her views; in fact a record of a talk she gave on Keats whilst she was living at Haggs Farm describes her as 'an ardent young socialist', and she continued to be active as a socialist and pacifist. She knew nothing of Lawrence's illness but claimed that in the months before his death she felt 'acutely drawn to him' and on the day of his death she thought she heard his voice say 'Can you remember only the pain and none of the joy?'

Jessie died 1st April 1944.

The following announcement was in the Nottingham Evening Post:

"WOOD - 1st April at 43 Breckhill Road, Woodthorpe, Jessie, the dearly loved wife of John Richard. Cremation Wilford Hill, Saturday, 4th, at 11 o'clock. No flowers by request."

Writing about Jessie

Texts referred to:

A Portrait of Jessie Chambers by Ann Chambers Howard in the Haggs Farm Preservation Society Newsletter 1986

Lecture by David Chambers – now reproduced in Miriam’s Farm, edited by Clive Leivers, Russell Press

DH Lawrence: A Personal Record by Jessie Chambers, 1980

Further Reading:

Jessie Chambers DH Lawrence’s Princess A Biography by Bridget Dunseith, 1998

Edward Nehls D.H. Lawrence: A Composite Biography, 1957

The Collected Letters of Jessie Chambers, The DH Lawrence Review 1979

So much has been written about Jessie being the model for Miriam in Sons and Lovers that I’m going to take something of a left turn, and take a look at another of Lawrence’s novel, The White Peacock, written two years earlier, and of certain things it suggests.

Lawrence was still at Nottingham University when he wrote The White Peacock, which, as Richard Aldington reminds us had:

“ …nothing to do with peacocks, white or blue-green, and everything to do with English people of the soil…”

Lawrence was a very complicated and contradictory young man (as he would remain as he aged) as he wrote his first novel, which he began in 1907, six years after meeting Jessie. Jessie would undoubtedly have a hand in the novel’s construction, and a presence within its pages, as would her brothers, and the home in which they lived, and the countryside around them.

This is the opening of Chapter One of The White Peacock:

“ I stood watching the shadowy fish slide through the gloom of the mill-pond. They were grey, descendants of the silvery things that had darted away from the monks, in the young days when the valley was lusty. The whole place was gathered in the musing of old age. The thick-piled trees on the far shore were too dark and sober to dally with the sun; the weeds stood crowded and motionless. Not even a little wind flickered the willows of the islets. The water lay softly, intensely still. Only the thin stream falling through the mill-race murmured to itself of the tumult of life which had once quickened the valley.”

Lawrence walked past that scene every time he went to Haggs Farm. But it’s also a description of Jessie: not a physical portrait, but one of her soul, and the inherited love of place and family, and of a darkness, a deep passion, held within her that will open itself — like the valley — to the sun one day: his day, Lawrence’s day. Lawrence saw her as part of the actual landscape — that she had somehow absorbed it, and it her — and of his literary landscape, which was something completely different: a place not yet created in full, but one that must have Jessie in it.

But it would not be as simple as that. How could it?

Please take a look at the website of one of our members Steve Newman, a writer from

Stratford upon Avon:

Jessie Chambers: DH Lawrence's First Love

Here's a short extract:

Ruth Templeton has written and performed a beautiful piece using Jessie's own words. It is available to buy at The DH Lawrence Birthplace Museum and The Breach House, Eastwood

Catherine Brown, vice president of the DH Lawrence Society mentioned that she had an elderly friend, Eve Leadbeater who went to tea at Jessie (Chambers) Wood's house.

Eve was featured on BBC Midlands News on July celebrating the fact that it was 80 years since she in England as a refugee This is her reminiscence of the meeting with Jessie.

TEA WITH 'JESSIE CHAMBERS'

Eve Leadbeater

I was born in Czechoslovakia on February 23rd 1931, and named Evelina Pragerova (Eva for short).

When I was eight I came to England on one of the last Kindertransport trains to leave Prague, in the summer of 1939. My brother was due to follow, but war broke out and I never saw my brother and my parents again.

My new 'mother' was Minnie Simmonds, a single woman living in Gedling, about four miles north-east of Nottingham city centre. She was the secretary of the local branch of the National Union of Teachers and had responded to the appeal from Nicholas Winton (organiser of the Kindertransport) for people to open their homes to the child refugees, which the union had passed on to its members.

I attended the primary school where Minnie was a teacher. Mr Wood, the Headmaster, was married to Jessie Chambers.

On one occasion, soon after I arrived, Minnie and I were invited to tea at the Woods' house on Breckhill Road, Mapperley. This happened eighty years ago, and I knew very little English so my memory of the occasion is hazy, but I do remember that the lady who was there, who I now know was Mrs Wood, was very welcoming and smiled a lot. She reminded me of an aunt of mine with her dark hair and eyes, and her smiles.

Some time after, when my English had improved, Minnie explained to me who I had been to tea with. I do remember that Minnie was rather shocked that the Woods had been to Russia, a Communist country!

I left Ashwell Street school at the age of 10 to go to grammar school and I don't think I ever met Mrs Wood again.

Note

Jessie wrote to Koteliansky in 1936 and mentioned that she and Jack had spent their August holidays in Russia and had 'a wonderful time'. Her interest in that country stemmed in part from her studies of the language with Janko Lavrin at Nottingham university in which she became quite proficient.